Ed Ney's "whole egg" of PR and marketing

by Hayes Roth, Landor

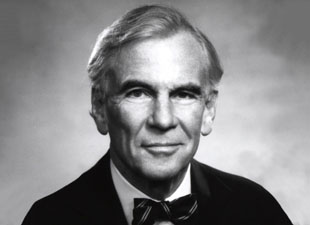

Since Ed Ney, former U.S. ambassador and past chairman of Y&R, passed away earlier this month, many wonderful stories have been shared among those who worked with him. These are all instructive and worth seeking out—he was an incredibly influential man to those of us who knew and loved him. But our focus here is on Ed's extraordinary accomplishments as an industry visionary and category disrupter. As Young & Rubicam Advertising's CEO, he saw an opportunity to change the game completely by engineering the acquisition of leading agencies across the marketing world, including Wunderman, Ricotta & Kline, Burson-Marsteller, Landor Associates, and others that soon joined Y&R's portfolio.

Today, mergers and acquisitions in the agency world barely constitute news, and large, diverse communications conglomerates are a fact of life for those of us in the business. Not so in the 1970s—this was the Mad Men era and back then it was all about the ads.

But Ed envisioned a different path: a marketing communications empire that crossed disciplines and borders, one that provided clients with integrated global marketing services linking advertising campaigns with PR initiatives and customer relationship programs.

Properly conceived and managed, these powerful tools would help generate awareness, attract customers, build brand credibility, and then nurture consumer loyalty and sustainable sales for clients. At the time it was a revolutionary concept. Yet Ed knew the idea was the right one, and he and his team gave it a name: the whole egg.

The past as prologue

These days, every major marketing communications organization promises integrated communications and ways to tap into the dizzying array of media channels. There are varying degrees of success when it comes to truly collaborative PR and marketing campaigns, of course, and brands of all stripes continue to struggle with creating consistent, cross-platform messaging.

That's why the fundamentals behind successfully building and executing a comprehensive marketing communications program are just as important now as when they were introduced in the 1970s.

There are many ways to get it wrong, but a few basics are essential to getting it right:

- Suspend your own agenda. The focus of any productive marketing initiative must be to solve the client's problem, not promote one's own agency or discipline. To pull off a well-coordinated campaign, one needs strong, highly motivated partners; make sure they are inside the tent all the way and feel welcomed and heard.

- Stay abreast of the full range of available marketing tools. No one can be an expert at everything, but successful marketers must remain open to learning the outside disciplines that best add to the mix and how to source and apply them.

- Communicate well and often. The means of sharing information within agencies and among clients may have changed, but the need to do so competently and inclusively has not. With all of the moving parts involved in modern communications, it is more critical than ever to keep all parties fully informed of developments, shifts in tactics, and swiftly evolving opportunities. This requires discipline, good, clear writing, and frequent contact, pure and simple.

- Measure results. The search for credible metrics in marketing communications has been a long one and we now have more resources than ever at our disposal. No one magic measure quantifies success (beyond, perhaps, the cash register), but there are now many sophisticated ways to evaluate which arrows in the quiver are hitting their mark. Learn how and when to use them appropriately.

- Share the glory. Integrated marketing efforts require a team to succeed. Teams need leaders, to be sure, but real leaders celebrate the team, not themselves (or their agency alone). A well-tempered and motivated communications team can move mountains if all are pulling together in service of a common goal.

I don't think Ed Ney would have argued with any of these principles in 1980. But they are no less difficult to follow today than they were then. Perhaps the difference is that now there really is no choice—our clients expect us to work this way. At WPP, we've even given this kind of thinking a new name:

horizontality. But whatever one chooses to call it—the whole egg or horizontality—it's here to stay.

This article was first published in PR News (27 January 2014).

prnewsonline.com